REFLECTING ON REFLECTIONS

Reflecting On Reflections

Michael Scheirl and his New Street Art

By Gerhard Charles Rump

City lights evoke modern romantic feelings. Times Square, Las Vegas, or, indeed, any other neon-studded city, like Seoul, Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Macao, Tokyo. The lights are reflected in the waters of rivers and lakes, in pools and fountains. And also by the wet streets after a downpour. This is a common aesthetic experience. A very popular one, too: There are about six or so pop songs dealing with the subject. Michael Scheirl’s series „Street Reflections“ take this as the starting pole in an ongoing artistic investigation, leading it far beyond the common and the everyday experience.

When we walk down the streets of a city, even in a small town, we are constantly beckoned on by a multitude of various signs. Traffic signs on posts as well as traffic signs on the surface of the streets, like pedestrian crossings, single or double yellow markings and so forth. Street signs (traffic signs) usually come in all three semiotic types, although most are either icons or indexes (acting according to the “pars pro toto” principle), only few are purely symbolic, i. e. non-depictive, non-iconic. Some, indeed, are even words. Michael Scheirl works with those in his „Street Paintings“-series.

In these images, worked on with original asphalt and original street markings, the street is changing its position, from the horizontal to the vertical, thus leaving the specific at least partly behind, gaining general importance, becoming a concept flowing over into form. The series demonstrates the great variability and the many variations of street signs, especially as Scheirl takes them from everywhere in the world. We find advertising, political phrases and all sorts of things discarded, forgotten, left behind. But all this changes in the process of being treated by the artist. A manhole cover, for instance, becomes a strong formal value; it changes from a manhole into the image of a manhole, from a functional object into an aesthetic one. It leaves its original context behind and is firmly established in the context of art.

This is a common technique in art since the advent of modernism. It was described as the “ostranenye”-effect by Victor Shklovsky (1893-1984), or alienation effect, also called estrangement. All of a sudden something doesn’t appear in its known form and context, but appears to be different. John Willet said (in “Brecht on Theatre”): “The achievement of the alienation-effect constitutes something utterly ordinary, recurrent; it is just a widely-practised way of drawing one’s own or someone else’s attention to a thing, and it can be seen in education as also in business conferences of one sort or another. The alienation-effect consists in turning the object of which one is to be made aware, to which one’s attention is to be drawn, from something ordinary, familiar, immediately accessible into something peculiar, striking and unexpected. What is obvious is in a certain sense made incomprehensible, but this is only in order that it may then be made all the easier to comprehend.” Such processes are abundant in the New Street Art of Michael Scheirl. (It’s New Street Art in opposition to common Street Art as Street Art brings art into the streets, whereas Scheirl’s New Street Art brings the street into art.)

An important aspect is the transitoriness, the changes street markings can undergo. Michael Scheirl says: “Everything is in constant flux, as merciless as time, flowing like traffic, mostly in pre-established patterns … A scenario experienced by everybody every day. However, in it, the artist detects an aesthetic field of tension which forms the basis for his play with structures, areas and signs.”

Almost all of Scheirl’s images contain this transitoriness; they take a moment out of time flowing and freeze it into artistic shape. The permanence given, in art, to a fleeting moment of reality does indeed constitute an aesthetic tension able to fire the beholder’s imagination.

Looking at the “Street Reflections”-series we notice that these images work on many different levels. First there is the information level (or informational focus). We may not learn everything about the image and its motif, but we see that what is reflected is either a colourful neon sign or signposts or slightly less colourful people. This is based in reality and the experience of reality, as people will only reflect on wet streets, preferably in puddles, and this implies rainy weather, in which people tend to wear less colourful garments. Or has anybody ever heard of a bright green mackintosh with red dots and purple stripes? There is this yellow raincoat around, mostly to be seen in Germany (where they call it “Friesennerz”, Frisian mink) but this is an exception.

The concept of style differentiates Scheirl’s work from others, and the aesthetic focus will lead us down the path of knowledge to an understanding of how the bits and pieces of the image work together and what effect they have.

On yet another level we will reflect the meaning, explore the semantic dimension, and by what syntactic or textual structures it is influenced. A simple example:

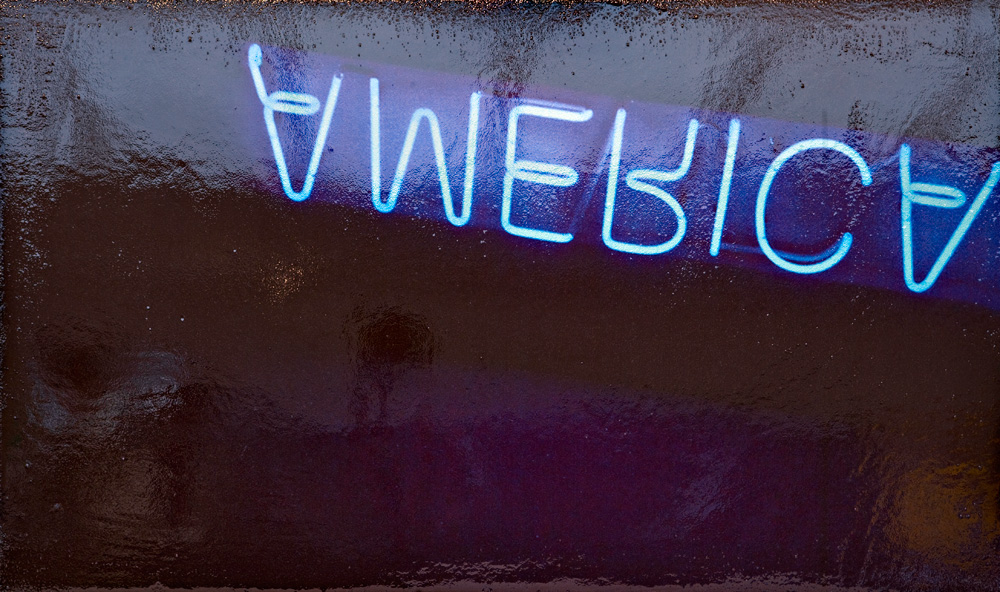

The image “Electric Blue” shows a dark grey surface, with an oblique bluish strip across the whole image, approximately covering the upper third of the image’s surface. Inside the area of the strip a blue neon light, bleeding into a light gray area, says AMERICA, but the letters are topsy-turvy and to be read from right to left – a complete mirror image. This pushes the door with the sign “interpretation” wide open.

Is America standing on its head? Has it been toppled by a crisis? Is America today just the opposite of what it used to be? Do we recognise America although it is just a reflection of itself? And so forth. It is quite clear that the word “America” is fascinating in itself, for all what it embodies, the reflected blue hue, standing out from the gray is conspicuous, and the obliqueness accounts for pictorial dynamism. And, after all, we don’t see the reflection on a wet street, rather we see it in the vertical, as an image and in an image. We aren’t above it, we find ourselves confronting it. We are standing close to the image, which we have to decode, to understand, reflecting on reflections. We may not be able to do that at first attempt, but maybe later. But then again – how sure can we be?

In the images of the “Street Reflections” those with reflected people are particularly intriguing, as they open a dialogue between the beholder and the person in the image, which is seen like in a glass, darkly (1 Corinthians 13, 12). Reflections in a puddle are all but crystal clear. The figures seem to be more like fleeting shadows, even though we can look at them for hours on end. The colours are subdued, the mood is melancholy. We find ourselves in a paradoxical situation, as we know that the real situation is transitory, whereas the time for the appreciation of the image is stable. We sense the character of the real, yet we know we are confronted by an image. How big is the difference between that which was and that what we see? Does the artist manipulate us? If yes, how far? More questions than answers? Maybe. And that is, after all, a form of fascination.

The “Street Paintings” follow their own agenda, but there are some similarities. Startling images are, for instance, those with the gridirons with amassed junk and debris (like cigarette butts) in the hollows. Of course the image draws on the concentric aesthetic of the real object, sharpening the view through partialness. Then there is the contrast between the symmetric grid and the existential random structure of the cigarette butts and other small items, all, however falling into place within the structure of the gridiron. And, beyond that, the pictorial interpretation of the process which lead to the constellation in reality in the first place. And this implies time. The cigarette butts having been dropped one after the other over a not too lengthy, not too short period of time. It also implies the presence of humans, although they aren’t seen in the image. Thus these images, by virtue of appearing in the vertical, also serve as a mirror in which we see ourselves reflected, albeit without the reflection of our faces and bodies.

IT´S NOT MY JOB

The course of time is also s subject in other “Street Paintings”, like in “It’s not my job” (No 387), which shows a manhole cover, which was overpainted with a yellow line twice. After the last lift up it was reset without regard to the yellow line, and this yellow line was painted over the lid without paying any respect to the older yellow line. This accumulation of blunders allows a reconstruction of the course of errors, which, in turn, is connected to a certain period of time. Time in a general term, as we have no way of knowing how long. Much longer than a couple of seconds, of course, but we don’t know whether we are speaking of two, four, or ten years. The whole image, shifted to the vertical, refers to general principles; it is a concentration of the core patterns of processes.

Of course Scheirl is a classical composer. The use of classical methods of composition, such as central figure, golden section and so forth, serves as the silver platter on which the new content, the new interpretation is served, in order not to confront the beholder with too much that’s new and also to endow the image with visual stability. Which, of course, appears to be important in a continually fluctuating world.

Of all the words we find in Scheirl’s images, the imperative “LOOK” is the most frequent. Sometimes it comes pure, sometimes in combinations with graphic elements or more words (“Look both ways”), sometimes in fragments, from which we learn that the right half of “LOOK” is “OK”. And we see that the double “O” seems like a pair of eyes. The words, also the “Look”, is, every now and then, combined with graphic elements which represent a certain pictorialness in reality; a pictorialness that is enhanced by the change to the vertical.

“Look” is an imperative. And what do we do when we see an image? We look. And if an image tells us to do what we are doing anyway, we are reminded of the visual imperative, but we are, at the very same time, also reminded that there is more to four letters than it seems. Letters, especially big ones in an image, have an aesthetic quality of their own. Joshua Reichert and Ferdinand Kriwet, among others, have shown this, also Horst Antes. And Robert Indiana. All in a different way without any reference to each other. Scheirl makes this lists of artists longer, and, again, without referring to any other artist’s work. The “Look”-images want us to concentrate on the painterly aesthetic of their appearance and thus point at qualities we constantly overlook in reality. It takes the switch to the vertical to better become aware of this.

X MARKS THE SPOT

In other street paintings, autonomous graphic elements put on a painterly coat and present a completely different stage production. In “X marks the spot” (No 390) a red “X” intersects a black line going across the gray surface of the image, positioned at approximately the golden section, whereas the red “X” has been shifted slightly to the right of the sectio aurea. A cunning way of introducing aesthetic tension into an image with very few elements. But we know from Kandinsky’s teaching that such effects are inevitable. Still it remains the choice of the artist to single out what serves his purposes best.

That is true in art in general. We always have to accept that when we see an image, we see exactly what the artist wanted us to see. If that weren’t the case, the artist would have changed it.

Scheirl’s works are the product of will and chance, of “readyfound” structures and the artist arranging, configuring, creating, designing, devising, fashioning, forming, moulding, and shaping them into exactly what he wants them to be.

In this case it all results in an enhanced awareness of our environment and what we can see there and of artworks, which explain the very nature of such processes.